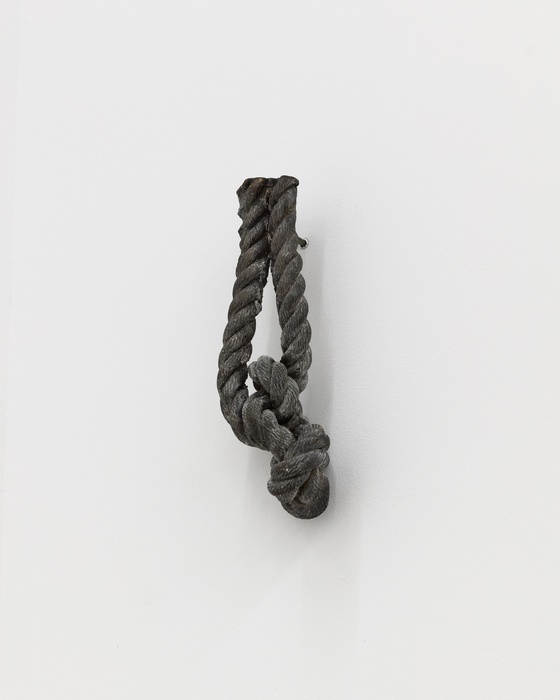

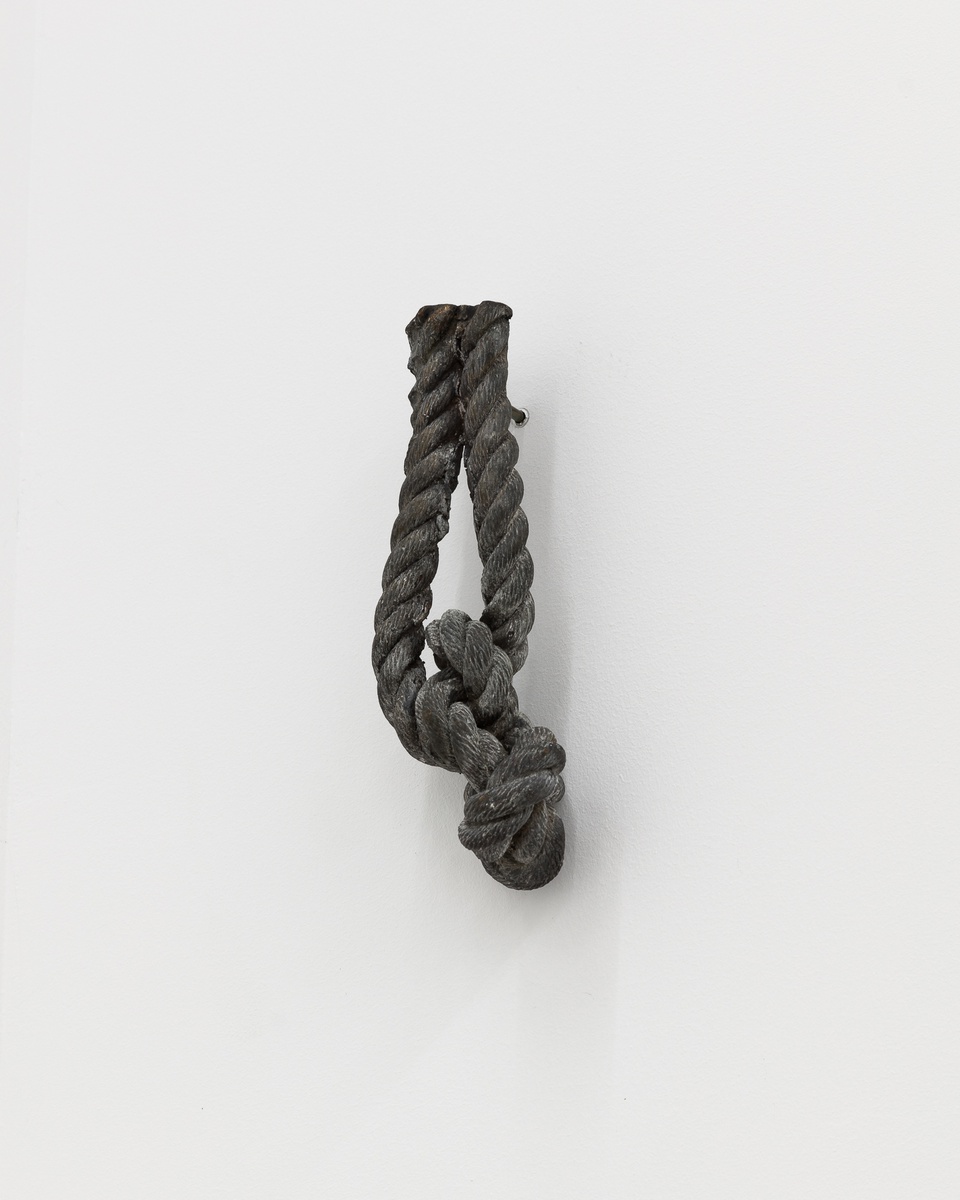

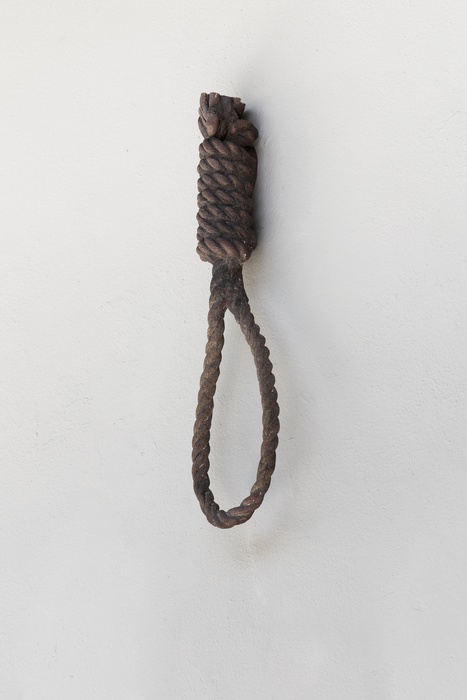

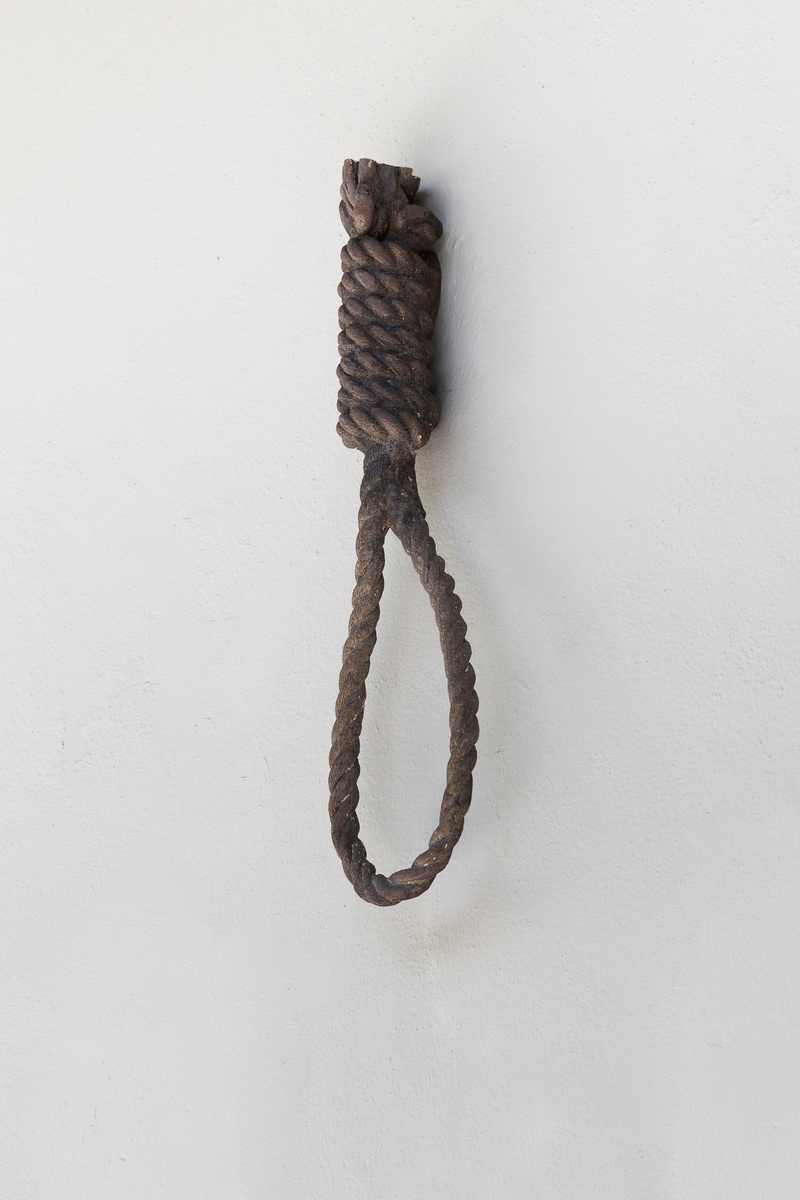

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Exhibition view, Jahn und Jahn, Lisbon, 2023

Opening: Thursday, September 28, 2023, 6–10pm

From Garland to Lições de Trevas A Few Remarks

The present exhibition of highly different works by Rui Chafes and Olaf Metzel evidently has a prehistory, which may explain why these so incomparable artists have mutually appreciated each other for so long and now are publicly showing several pieces they jointly selected for the first time.

Lisbon was Cultural Capital of Europe in 1994, the year the two artists met each other, despite their great age difference of 14 years and divergent interests and aesthetic approaches. Then, too, Metzel had made a name for himself not only in West Germany through one-man and group shows, whereas Chafes had just completed his studies with Gerhard Merz at the Düsseldorf Academy the year before. During his stay in the Rhineland he had learned German, enabling him to translate fragments of Novalis, who had fascinated and impressed him so deeply, into Portuguese for the first time. His fruitful immersion in the ideas of Romanticism would prove to be crucial for Chafes’s aesthetic development and approach.

For his project in Lisbon back then, Metzel had made a suggestion that still seems baffling today. The sketches shown in the exhibition reflect the provocative nature of his project. The Arco da Rua Augusta is an impressive triumphal arch that links the street of this name with Praça do Comércio. Planned shortly after the devastating earthquake of 1755, the erection of this symbol of Portuguese national pride had to wait until the 19th century. The Baroque ornament with the ample figure of Gloria at the top leaves enough space for the four large sculptures of famous personalities, including Vasco da Gama, who led the first European voyage to establish a direct sea route to India, and the Marquês de Pombal, to whom the reconstruction of the city was largely owed. Their figures face the great square that opens out to the Tejo River, at its center the equestrian statue of José I from the 18th century.

Metzel focused on the back side of this pompous staging of key events in Portuguese history and entitled his suggestion Garland. He altered reproductions of historic plans and supplemented them with his own drawings. Along with a small model, the depictions show that his project related to the terrace at the back of the arch, a favorite tourist viewpoint. Visible only from Rua Augusta, two ropes stretch between posts on the balustrade just above the double pilasters flanking the great gateway. Executed in bronze, very heavy and with a greenish patina, the “garland’s” message is easy to decipher. It has nothing to do with the garlands of sculptured flowers and fruit on the front of the arch. For centuries, sea trade and the associated colonialism formed Portugal’s economic basis. Double bollards and heavy ropes were needed to moor a ship in harbor, a job that required stamina and skill in face of shifting currents and weather. This was the barely noticed, harsh underside of the profitable sea trade. Metzel pointed this out with his ironic suggestion and lent the triumphal arch with its historic figures a different, critical thrust, a “garland” that provided food for thought about the plethora of nameless laborers involved. This message was understood in 1994, and the project was put into practice, apparently to the approval of amateur painters, caricaturists, and tourists to this day. A few further works in the show make reference to his Garland, including Metzel’s Knots, Braids and Knitting Model. In contrast, Chafes’s Sombra dourada I – III elicit no more than vague formal correspondences. This also holds for Durch mein Blut, IV, V, VI and Nada é aqui, I and II. That Metzel possesses the skills of a traditionally trained sculptor is evident from the portrait bust Turkish Delight. The closed, compact form finds an equivalent in Fina camada de gelo, I and II by Chafes.

Much the same can be said of a juxtaposition between Chafes’s Lições de trevas IX, XII and Metzel’s Collecting Point. Yet these are no more than formal analogies that cannot hide the fact that the two artists take fundamentally different positions. This discrepancy is made obvious by various works in the exhibition. Baise moi by Metzel was done in 2019 and refers to the novel of that title by Virginie Despentes, published in 1994 and filmed six years later. The story tells of a socially marginalized young woman who is raped, but joins with a friend to take cruel revenge on the male sex. Metzel’s large-scale, wall-filling collage conveys this in terms of motif and form without becoming too blatant. The two typographic works with the title kaputt very directly underscore the gap between Metzel and Chafes. Curzio Malaparte’s epoch-making anti-war novel, a monstrous panorma of pogroms and partisan battles, was published in 1944 and immediately became a bestseller. Referring straightforwardly to this work in 2020 seems to presage Russia’s attack on Ukraine two years later.

When we recapitulate the many shows Metzel mounted in abandoned spaces, galleries, museums and streets and public squares since the early 1980s, we have the impression of looking at what Wieland Schmied in 1995 called “relics of a battle”. In fact, viewed superficially, the artist might seem to have run amok, concerned only to demask, deform and demolish. This impression also long determined the reception of the controversial sculpture 13.4.1981. Executed in 1987, it was publicly shown that same year on the Berlin Sculpture Boulevard organized on the occasion of the city’s 750th anniversary. Like a signet for many other Metzel works, 13.4.1981 triggered violent and largely negative reactions. The work was basically a large-scale montage or collage, comprising what the artist called a “complete department store catalogue of mundane aesthetics, unhierarchical and laconic” and linked with the current social situation. Yet its process of stacking and amassing not only reflected a reverence for Dada, Surrealism and Decollage, and hardly bore parallels with Fluxus and Nouveau Réalisme.

When we review Metzel’s oeuvre to date, one does not have the impression of dealing with the relics of sheer destruction. The piece 112:104, for instance, consists of the apparently randomly arranged remnants of a basketball court, perhaps the frightening results of the demolishing of the premises by boorish fans of the losing team. On closer scrutiny, we find that this destructive robbing of function transforms the work into a carefully balanced symbol. This symbol, as W. M. Faust points out, indirectly alludes to Caspar David Friedrich’s Arctic Sea of 1821/4, also known by the title Crushed Hope. Other commentators are put in mind of the Raft of the Medusa, 1818/9, by Géricault. As far as we can tell today, almost all of Metzel’s works play on the contrast between destruction and construcion, and ultimately on that between reality and art. Historical, social and political issues underpin all of them, even though this impulse is usually not immediately recognizable, becoming apparent only after long observation and reflection. As a sculptor Chafes employs iron almost exclusively, continuing a great Iberian tradition. Yet great weight and enormous resistance to pressure and tension are not immediately apparent in his variation-rich and black patinated pieces. The brittle, virtually primal aspects remain unaddressed as well. Traces of working have been largely erased from the sheets and rods, bands and tubes. Conventional notions of the character of iron sculpture are wiped away with an easy touch. The faultless surfaces in matte black seem to rob the alien yet fascinating configurations of their material character. The range of Chafes’s works extends from compact forms to filigree networks and veils. A number of them give the impression of enigmatic configurations made of shadows, or occasionally silhouettes that unfold in space. Especially the circumstance that many works hang on walls or in trees, or appear to hover in the air, lends them the character of potential motion or ephemeral volatility. These are mysterious, often weighty yet seemingly transient objects, which despite their artificial character evoke a suggestion of vanished vitality. These are configurations whose metaphoric nature undermines the solid objectivity of the sculptures, such that their forms appear ambiguous and not coeval with sheer visual presence. The oscillation between alienation and abstraction, between biomorphic motifs and rational principles of order, leads to an emphasis on the objectivity or facticity of the sculptures while more or less depriving their physical appearance of all consistency and clarity. It is precisely this paradox that lends his sculptures a very special and inimitable place within contemporary art. The enigmatic seems a matter of course for Chafes, and the apparently straightforward takes on enigmatic aspects the longer one looks, a virtually magical dimension. Thanks to their auratic presence, the dark structures obviously make reference to a sphere beyond pragmatism, economy and functionalism, that is, to a region beyond utility and instrumental reason.

A number of the sculptures, oscillating between impressive physical presence and subcutaneous mystery, evoke a counterworld to everything that is the case, and thus indirectly to disturbing premonitions of loss, mourning and sometimes the fear of death. Instead of drawing attention to a past of aesthetic commitments and ethical values, the artist’s eye apparently surpasses the horizon of a narrow, often one-dimensional life world. What additionally ensures his oeuvre of outstanding status is the eminent quality of his works. Characteristic of many of them is moreover a positioning in a specifically architectural setting. This was impressively apparent when a number of Chafes’s sculptures were installed in 2013 in a few of the Sassi di Matera (surviving Old Stone Age cave dwellings, a World Heritage Site), but also in 2018, when several works were installed or hung on streets and squares in Bamberg and environs.

Metzel represents the opposite position in an impressive and convincing way. This becomes apparent not least in works he created for the public domain and which triggered very heated controversy. Chafes’s works, in contrast, are marked by a programmatic distance from everyday life, and a no less decided statement concerning the autonomy of art. His tension-filled and fruitful involvement with the oeuvre of Riemenschneider on the one hand, and Giacometti on the other, has made this amply clear. Metzel takes an entirely different tack, though his interests are similarly wide, combining enthusiasm for the architect and sculptor Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439 – 1501) and the Bézier curve. This is a parametrically modeled curve that represents an important tool in describing free-form curves and surfaces. For all their mutual appreciation and friendship, the distance between the two artists’ ideas and convictions, as reflected in their work, could hardly be greater.

Armin Zweite