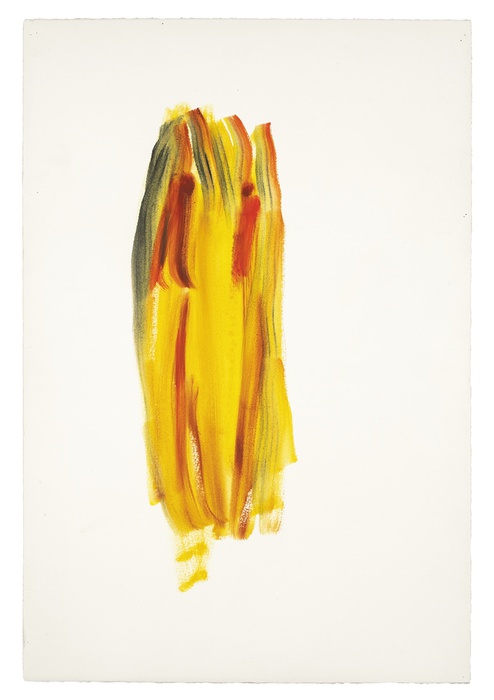

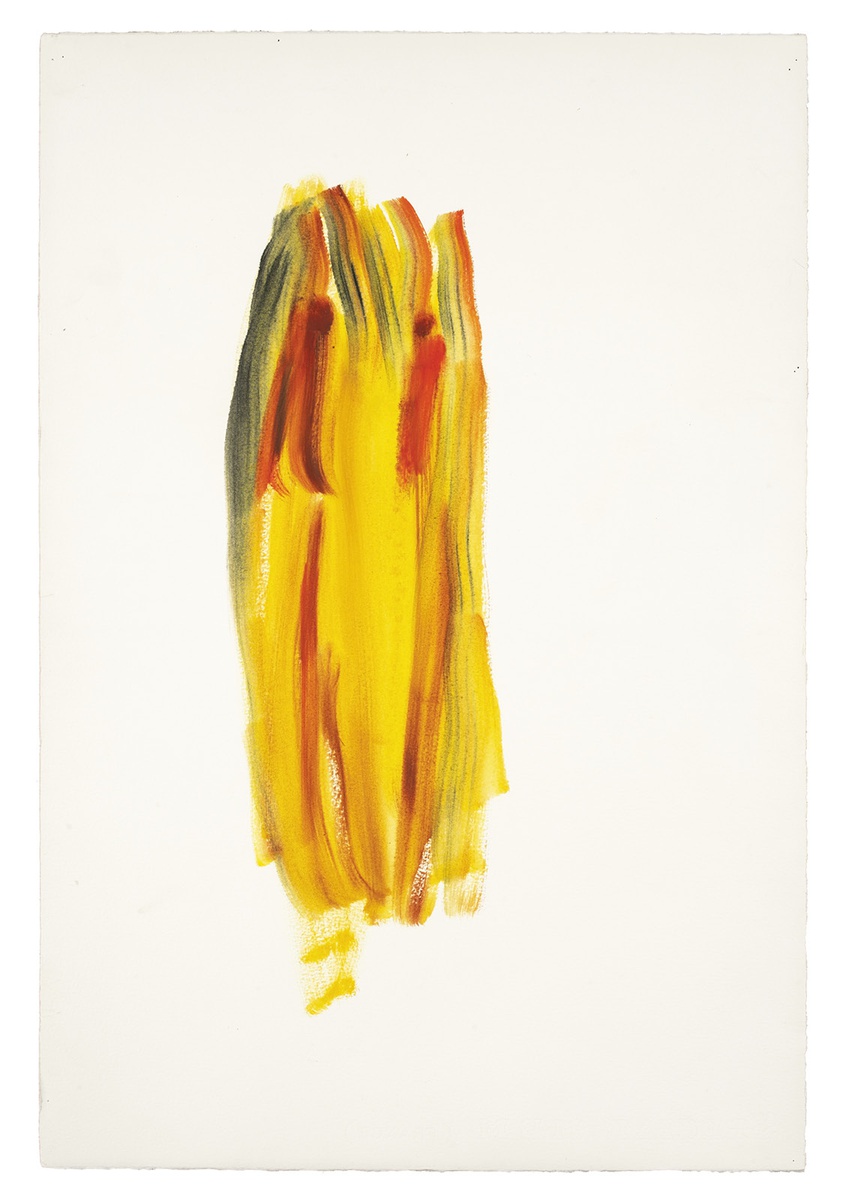

Oil, acrylic on paper

57 x 38 cm

Opening on Thursday, January 29, 6–8pm

Henri Michaux

For All and Against Everyone

“No creature,” Saint Thomas observes, “can attain a higher degree of nature without ceasing to exist.”(1)

To begin with Michaux is to be doomed to failure. It is with him as with accident. Any thought, any impulse, any confidence disintegrates at once. “I write to go through myself all over. Painting, composing, writing: going through myself. That is the adventure of being alive.”(2)

Accident and disintegration are his formula, which is permeated by an antimatter that unremittingly pushes to penetrate the finest capillaries of existence. Michaux found a way to outline a record of life that neither reflects a stigma nor pursues a logic. Rather, it is an investigation, in writing as in drawing, into the moment at which we lose our orientation and start stumbling so that our existence impacts upon the reality we have inflicted on ourselves. Michaux was a seeker throughout his life, one who, in drawing, labored to uncover the traces both of the marks of painting and of his own creative failure.

His quest goes back to the Paris of the 1920s and 1930s; to a city that, at the time, was the center of the world of poetry and painting. A native of Belgium, Henri Michaux (1899–1984) had already built a successful career as a writer when he discovered drawing for himself. During extensive travels through Latin America, India, and China between 1927 and 1937, he produced his first works on black paper. In the 1940s, his output in visual art picked up momentum, yielding extensive series of works on paper. In the 1950s, he created his widely noted Mouvements drawings, followed by the Mescaline. Numerous publications on Henri Michaux have already been devoted to the turning points in the artist’s life and attempted to categorize his oeuvre on the basis of the works’ specific geometries.(3)

For our purposes, it is much more important to understand what his drawings are: “Books are boring to read. No free circulation. You are requested to follow. The path is predetermined, a single one. / The picture is completely different: immediate, total. Left, and right too, into the depth, ad libitum. / Not one path, a thousand paths, and the spaces in between are not marked. As soon as you wish, the picture is altogether new. In an instant everything is there. Everything, but nothing is yet known.”(4)

The poet does not think of the drawing as a self-contained work. He is much more interested in serialism and the understanding that every movement that is put on paper is connected to a never-ending series of exercises and thoughts that cannot be disentangled. Everything linear was repugnant and suspicious to him; in short, he painted “to decondition myself.”(5)

To wean himself off and deconstruct himself again and again.

In their immediacy and directness, their serialism and ephemerality, the latter are exemplary of the series of works reproduced here. Michaux, according to his good friend and colleague E.M. Cioran, was someone who “marshals every resource in order not to achieve his object.”(6) He was interested not only in drawing, but also in the support medium, the sheet of paper that interacts with the watery pigment. He would sometimes moisten the paper, and the reactions of the fibrous material almost resembled a living thing’s responses to a counterpart. The flow of the watercolor provided a clue to a form that Michaux could use as a point of departure, a holding-on to accident. This approach, what he called “dissolution,” led to series of works that he created in marathon sessions which sometimes lasted days until he was utterly exhausted; moments in which the painting hand eluded conscious control and a grid of signs emerged that merge endlessly into one another.

Reprinted in the appendix to the catalogue accompanying an exhibition at Galerie Daniel Cordier in Frankfurt in 1959 is an unsigned note by Michaux: it explains why the works have no titles—they are “improvisations without subject matter, witnesses not to structures but to movement,” and if they needed a title, it would be: “Moment 1, Moment 2, Moment 3, Moment 4, 5, 6, and so on.”(7)

Although Michaux tried to keep his artistic and literary oeuvres strictly separate, he pursued the same practices in both.

“A moment returns, leaves behind, aligns itself, a subsequent moment, a moment descends, a related moment, a moment to be seen again, one more moment,” he wrote in 1967, as though trying to supplement, if not reclaim, the untitled series shown in Frankfurt eight years earlier with a series of words, of the unvarying word “moment.”(8)

In the exhibition catalogue that Fred Jahn published in 1987, three years after Michaux’s death, the writer Michael Krüger suggested the place to which we should assign the artist: “When people will look back very soon on the literature of this ill-fated century, then, alongside the great epic monuments and their desperate search for a social truth, smaller writings will very soon come into focus whose fresh charm lies precisely in giving a wide berth to everything to do with society and its filiations.”(9)

The same will probably be true of Michaux’s drawings and pictures in small formats. A confrontation with all that is incongruous in inward as much as outward existence. A reprise of the question of a “higher degree” that we will never attain yet can strive to approach. This existential stance is timeless and, in its clarity and radicalism, could hardly be more urgently relevant today. Michaux must be seen and read, preferably in daily doses. Without him we risk failure.

1.) E. M. Cioran, The New Gods, trans. Richard Howard (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 45.

2.) Darkness Moves: An Henri Michaux Anthology, 1927–1984, trans. David Ball (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 330.

3.) See, for instance, the review in the exhibition catalogue Henri Michaux: Momente, edited by Dieter Schwarz for the Kunstmuseum Winterthur in 2013.

4.) Henri Michaux, Das bildnerische Werk, edited by Wieland Schmied (Munich: Verlag Fred Jahn, 1993), 63.

5.) Henri Michaux, Emergences/Resurgences, trans. Richard Sieburth (Milan: Skira, 2000), 9.

6.) Peter Hamm, “Ich bin durchlöchert,” https://www.zeit.de/2006/50/L-Michaux (accessed January 1, 2026).

7.) Henri Michaux: Aquarelle, Temperabilder, Federzeichnungen, exh. cat., February 3–March 15,1959, Galerie Daniel Cordier, Frankfurt am Main, 1959, quoted in Henri Michaux, Momente, ed. Dieter Schwarz, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 2013, 15.

8.) Momente, Durchquerungen der Zeit, 1967 (Munich: Hanser Verlag, 1983), 80.

9.) Henri Michaux, Bilder Aquarelle Zeichnungen Gedichte Aphorismen, ed. Michael Krüger (Munich: Verlag Fred Jahn, 1987), 9.